About Us

Shifteh completed a Fine Arts Degree at Acadmey in Italy and has given painting clasess to many students as well. He had exhibitions throughout Iran,Italy,France,and the U.S.A. He has recently taken up residency in London and has an exhibition at the Emerald Center London, 1993 and at wimbledon library 1994.

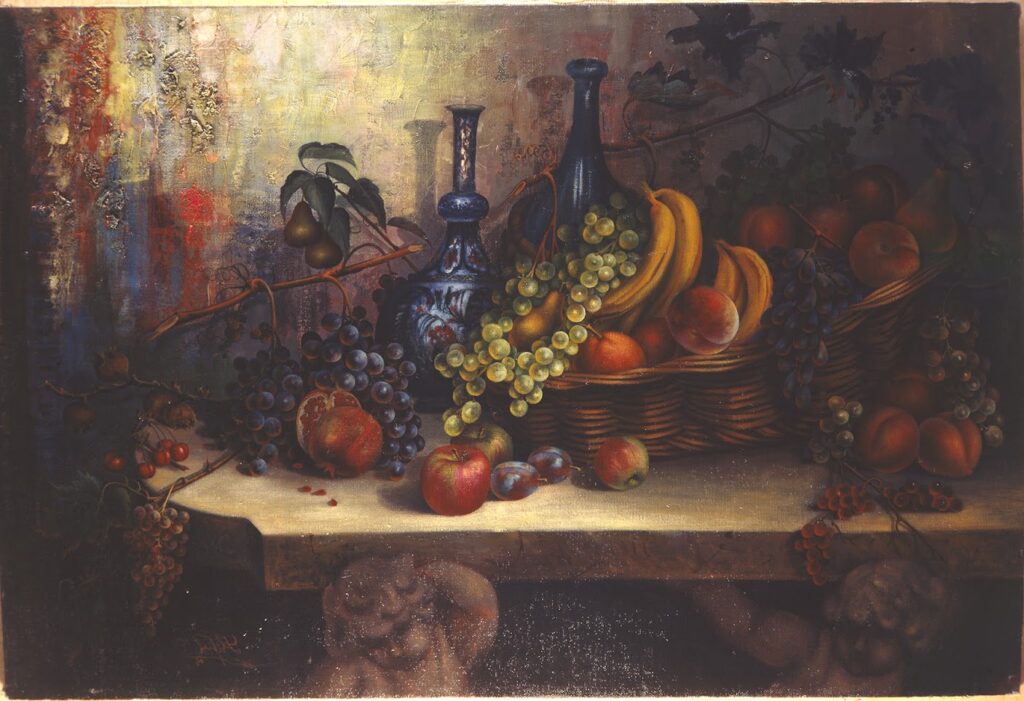

His art work consists of many contemporary pieces, including landscapes of places he has lived and visited.some of his larger oil paintings are inspired by persian 18th century history periods. Shifteh has worked on the vatican in Rome restoring ceiling paintings . Some paintings called Alfresco were restored for the King of Sweden”s house in Stockholm. Most of these restored paintings for the King were then left to the Swedish museum.

The Beginning

Professor Shifteh is a renowned painter and restoration expert specializing in antique paintings and sculptures. He earned his Fine Arts degree in Italy and has showcased his versatile talent in exhibitions across different countries. Proficient in classical, impressionism, realism, and abstract art, he is currently focused on creating captivating family portraits.

His artistic journey began in childhood, earning acclaim for his pencil drawings featured in “Majeleh Etelaat Koudekan” at just eight. By 10, he apprenticed under Behzad, the eminent miniature artist, later exploring oil paintings under Anoush Rahnavard. At the tender age of 12, Shifteh’s artistic journey reached another pinnacle when he was accepted into the art of Kamal-ol-Molk, marking a significant chapter in his education and artistic development. As time unfolded, Shifteh’s passion led him back to his first love – painting.

It signalled the beginning of Safar’s lasting impact on the art scene, showcasing the seamless synergy of inherent talent, mentorship, and dedicated commitment.

During his era, Safar’s art exhibitions obtained significant acclaim, earning praise from both the public and the imperial court of Iran. Queen Farah, recognizing his talent, granted him a gallery on Farah Shomali Avenue in Tehran named “Shifteh.” Alongside exhibiting, he imparted his artistic knowledge to students. Following the Iranian Revolution, Safar, compelled to close his gallery, relocated to Italy.

1979

In 1979, he enrolled at the Academic Bell Art in Rome, expanding his painting expertise. Later, In 1982, he enrolled in the Istituto del Restauro in Florence, honing his skills in the restoration of antique paintings. By 1990, he delved into sculpture studies at the Academic Bell Art. Following these educational pursuits, he founded his studio, thoughtfully named “Studio Architetto Shifteh”.

1994

In 1994, he received a commission from the Swedish company Ullenius to travel to Sweden and restore fresco paintings in the King of Sweden’s palace. Subsequently, he was invited to reconstruct one of Sweden’s oldest theatres.

With exhibitions spanning Iran, France, Italy, and the USA, Safar’s contemporary artwork has left an indelible mark. Renowned for restoring ceiling paintings in the Vatican, many of his works adorn Swedish museums. Upon arriving in London, he established his atelier.

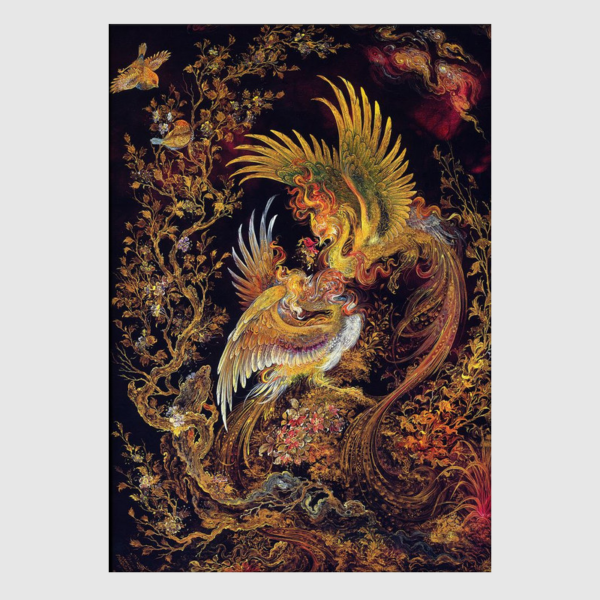

Persian art

Persian art or Iranian art (Persian: هنر ایرانی, romanized: Honar-è Irâni) has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painti

From the Achaemenid Empire of 550 BC–330 BC for most of the time a large Iranian-speaking state has ruled over areas similar to the modern boundaries of Iran, and often much wider areas, sometimes called Greater Iran, where a process of cultural Persianization left enduring results even when rulership separated. The courts of successive dynasties have generally led the style of Persian art, and court-sponsored art has left many of the most impressive survivals.

In ancient times the surviving monuments of Persian art are notable for a tradition concentrating on the human figure (mostly male, and often royal) and animals. Persian art continued to place larger emphasis on figures than Islamic art from other areas, though for religious reasons now generally avoiding large examples, especially in sculpture. The general Islamic style of dense decoration, geometrically laid out, developed in Persia into a supremely elegant and harmonious style combining motifs derived from plants with Chinese motifs such as the cloud-band, and often animals that are represented at a much smaller scale than the plant elements surrounding them. Under the Safavid dynasty in the 16th century this style was used across a wide variety of media, and diffused from the court artists of the shah, most being mainly painters

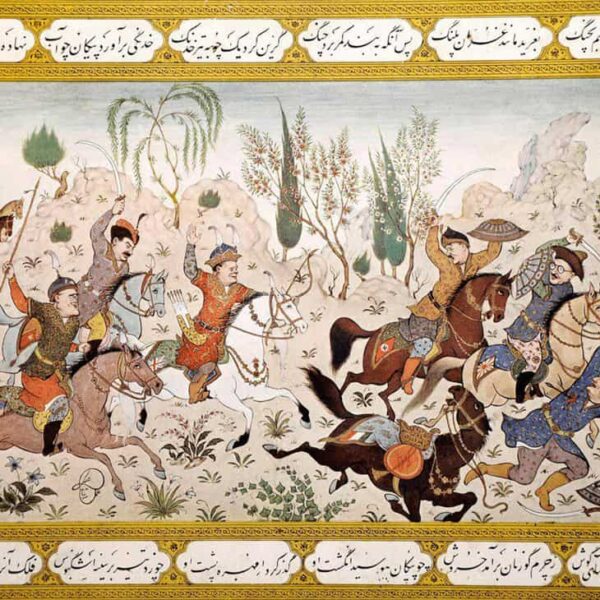

Persian miniature

A Persian miniature is a small painting on paper, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a muraqqa. The techniques are broadly comparable to the Western and Byzantine traditions of miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. Although there is an older Persian tradition of wall-painting, the survival rate and state of preservation of miniatures is better, and miniatures are much the best-known form of Persian painting in the West, and many of the most important examples are in Western, or Turkish, museums. Miniature painting became a significant Persian genre in the 13th century, receiving Chinese influence after the Mongol conquests, and the highest point in the tradition was reached in the 15th and 16th centuries. The tradition continued, under some Western influence, after this, and has many modern exponents. The Persian miniature was the dominant influence on other Islamic miniature traditions, principally the Ottoman miniature in Turkey, and the Mughal miniature in the Indian sub-continent.

The tradition grew from book illustration, illustrating many narrative scenes, often with many figures. The representational conventions that developed are effective but different from Western graphical perspective. More important figures may be somewhat larger than those around them, and battle scenes can be very crowded indeed. Recession (depth in the picture space) is indicated by placing more distant figures higher up in the space. Great attention is paid to the background, whether of a landscape or buildings, and the detail and freshness with which plants and animals, the fabrics of tents, hangings or carpets, or tile patterns are shown is one of the great attractions of the form. The dress of figures is equally shown with great care, although artists understandably often avoid depicting the patterned cloth that many would have worn. Animals, especially the horses that very often appear, are mostly shown sideways on; even the love-stories that constitute much of the classic material illustrated are conducted largely in the saddle, as far as the prince-protagonist is concerned. Landscapes are very often mountainous (the plains that make up much of Persia are rarely attempted), this being indicated by a high undulating horizon, and outcrops of bare rock which, like the clouds in the normally small area of sky left above the landscape, are depicted in conventions derived from Chinese art. Even when a scene in a palace is shown, the viewpoint often appears to be from a point some metres in the air.